Campbell's Soup Investing: Product vs Concept

When you buy a can of soup, you are actually investing.

You are exchanging part of your ‘Net Cash Flow’ for something you will consume in the future. That is the definition of an asset; a thing you hold now, acquired by the current surplus you’ve generated, held for consumption sometime in the future. How far in the future? When’s the sell-by date? That’s your limit.

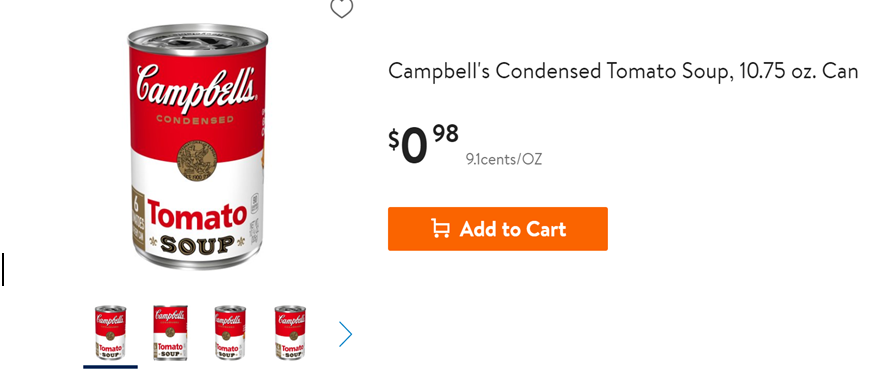

There are two problems with this asset, when you’re hungry, you pull out the can opener and it’s gone; now you have to spend your hard earned net cash on another type of sustenance (maybe chicken noodle this time…). Income producing assets (the subject of a later post) can provide you with the cash flow needed to keep you knee-deep in soup (so to speak). It is also a perishable asset, it loses its usefulness after about 2 years (the typical ‘sell by date’). What if it didn’t have a sell-by? How would it have performed as an investment (just play along, there’s a point to this at the end…)? Today a can of Campbell's Tomato Soup costs $0.98 at Walmart (see above*) and it’s been for sale for 120 years. Below is a graph of the price since 1898**:

That’s about 120 years of soup history, with a starting cost of 10 cents and a current price of 98 cents. An increase of approximately 1.85% per year is not the most exciting return one could wish for. But buy it in 1970 (just before the US went off the gold standard) and you’ve made 4.6% per year. Still not an earth-shattering return for its time.

That’s about 120 years of soup history, with a starting cost of 10 cents and a current price of 98 cents. An increase of approximately 1.85% per year is not the most exciting return one could wish for. But buy it in 1970 (just before the US went off the gold standard) and you’ve made 4.6% per year. Still not an earth-shattering return for its time.

Now you’re probably thinking, ‘investing is pretty boring if all I’m doing is buying stuff like soup’ and watching it go up a couple percent a year. But remember, soup is a combination of commodities that produce a known product. The ingredients are known and so is the product.

What about investing in concepts?

This is where capitalist economies really exert their power. Start-ups are concepts at first blush, and every new product (and service for that matter) starts as a concept. The tyranny and discipline of the marketplace determine whether concepts become companies or new asset classes (hello bitcoin?). There is an ‘art’ in the creation of a new business or product, and it is down to the ability of the creator to convince the marketplace of the validity of the concept (and to plonk down hard earned cash to fund the transition from concept to product).

So consider the greatest ever ‘investment’ in tomato soup.

In 1962 gallerist Irving Blum showcased a young Andy Warhol’s print series of, you guessed it, 32 Campbell's soup cans. Art reviews were not kind and only 5 were sold. Blum managed to keep the series together and paid Warhol $1,000 for them (in $100 installments). For the record that would have purchased approximately 10,000 cans of Campbell's Tomato Soup in the day.

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79809

This particular concept went, in its own way and for its time, viral. It was a visual representation of the materialistic times and a commentary on the slightly vacant nature of the ‘modern’ art being produced. They are now iconic symbols and are requisitely valued. How much? The Museum of Modern Art purchased the set and compensated Mr. Blum $15 million in 1996 and estimates of current value are in the neighborhood of $200 million. Get the full story from the Vanity Fair article below:

https://www.vanityfair.com/style/2018/11/andy-warhols-campbells-soup-paintings-exhibition

So how did Mr. Blum do on his ‘investment’?

An original $1,000 cost, held for 34 years and sold for $15 million reflects an annual return of 32.7%; if Mr. Blum had held it to today (where it is conservatively valued at $200MM) his return on investment would have been approximately 24% per year.

That is the power of a concept taking off and assuming some level of high value in greater society of the economy; but for the one big winner like this, there are thousands of ‘fallen angels’. Recently, the concept of ‘WeWork’, changing the way people work and interact gained a certain value in the marketplace, today it is less so.

By the way there is an investor who has rivaled the Warhol return over time, Warren Buffet. Berkshire Hathaway stock was trading at $11.50 in 1964 and today a single share is worth $328,300, a 21% annual return.

Mr. Buffet looks at the underlying value of a business and tries to buy it at a discount (a style called value investing) and would never have considered the Warhol an investment, more a speculation.

We will examine different investing styles over time but right now it’s worth asking yourself:

- What is my investing style? Do I want to find the concept that will produce massive returns over time, with the understanding that many of those concepts will fail?

- Or am I happy slowly aggregating cases and cases and cases of ‘soup’. Looking to buy them when they’re historically cheap and maybe selling them to hungry folks when the price is higher? It’s not super-sexy, but there’s always a meal at hand.

© 2019 Haddam Road Advisors. All rights reserved.

Brian Kearns, CPA

Haddam Road Advisors

Financial Planner / Portfolio Manager

1603 Orrington AveSuite 600

Evanston, IL60201

Ph: 312 636 3067

www.haddamroad.com

NOTE: This is being provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell any specific securities. Past performance is no guarantee of future results and all investing involves risk. Index returns shown are not reflective of actual performance nor reflect fees and expenses applicable to investing. One cannot invest directly in an index. The views expressed are those of Haddam Road Advisors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Mutual Advisors, LLC or any of its affiliates.

Investment advisory services offered through Mutual Advisors, LLC DBA Haddam Road Advisors, a SEC registered investment adviser.

** https://politicalcalculations.blogspot.com/2015/06/the-price-of-campbells-tomato-soup.html#.XdcuAOhKjD4

- April 2025 (4)

- March 2025 (2)

- February 2025 (1)

- January 2025 (8)

- December 2024 (1)

- November 2024 (8)

- October 2024 (6)

- September 2024 (1)

- December 2023 (1)

- November 2023 (1)

- October 2023 (1)

- August 2023 (1)

- May 2022 (1)

- February 2022 (1)

- September 2020 (1)

- August 2020 (2)

- June 2020 (1)

- February 2020 (1)

- January 2020 (1)

- December 2019 (4)

- November 2019 (2)

- October 2019 (1)

Subscribe by email

You May Also Like

These Related Insights

Haddam Road in the News: Capitol City Now

The Why, What, and How of Financial Planning: Standards of Care and the Planning Grid